Some Observations Concerning American Philanthropic Contributions to Greece’s War of Liberation of 18211

by Dr. Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou

Whenever one deals with the subject of the Greece’s war of liberation it must be recognized that after 1453, the Greek people struggled for centuries to free themselves from foreign rule in a wide variety of places and circumstances. Contrary, to the way the nineteenth century “revolutionary” 1821 events are usually presented, it is my view that there was as much continuity as discontinuity with previous revolts, and that the ingredients for success were both accidental and timely. Additionally, as it has become increasingly clear, one must understand not only the European ideological context of the time, but the social factors within Greek society, and the dynamics of local Ottoman political authority, in order to explain the outbreak and its aftermath. Regional variation was also a factor, and helped determine why efforts in the north quickly failed while those in the south were sustained.2

Greece’s ultimately successful 1821 revolt, was a complex affair that lasted almost a decade, and had an immediate and devastating impact upon the lives and material well-being of its people.3 It is difficult for us to imagine the sacrifices and desperate situation the fighters of 1821 faced. By 1826 it looked like as if the war was lost, and that after five years of struggle their bid for freedom from Ottoman rule would be over. It is hard to see how without foreign intervention, the contest would have resulted in the formation of a Greek state at that time.4 As is well known, this foreign military intervention resulted in a new nation-state that was officially independent, but in reality subject to a wide variety of internal and external limitations because of its dependence upon French, British and Russian support on a case by case basis. Additionally, the war did not result in any immediate revolutionary change in the structure of Greek society, but in fact began a process which eventually brought about deep institutional and social changes and a redistribution of power between local and diaspora elites.

There is much that remains little understood about the progress of the war and its ultimate result, and in particular there is a great deal of inaccurate popular information and mythmaking that circulates every March 25th.5 However, it is not my purpose here to go into these matters but to call attention to one aspect of the role that the United States played in that momentous struggle, and in particular the crucial contribution made by the American people in saving thousands of Greek lives. It is a story that has gone largely unnoticed, but one that deserves to be better known because it a broad sense it has many parallels to subsequent Greek-American relations.6 My observations are intended to elaborate upon and supplement what I wrote in a previous study published to commemorate the 175th anniversary of the war for liberation which brought together a large selection of American documents illustrating the various aspects of United States involvement.7 It is my hope that the few comments presented here will help stimulate further research and capture the imagination of some young scholar who will produce a comprehensive account of this important philanthropic effort and of the actions of small band of American philhellenes who were there and responsible for its successes.8 Most notably, a detailed study of George Jarvis is especially lacking, because unfortunately, the pioneering work of George Arnakis which he did not live to complete has not been supplemented and followed up upon.9 In many ways, Jarvis was as important to the Greek cause as Samuel Gridley Howe, yet he has not received the attention that Howe has. Additionally, one has to note that Johnathan P. Miller, another of these American philanthropic heroes has received even less attention than Jarvis. I hope that I will be able to contribute to correcting this imbalance in the near future.

As is well known, the media campaign concerning the Greek revolt led by prominent philhellenes such as Edward Everett captured the American popular imagination shortly after 1821. This phenomenon was called “Greek fever” or “Greek fire” by the popular press and was widespread although more concentrated in the northeastern United States. Between 1821 and 1826, hundreds of articles were written and reprinted in American newspapers, and thousands of ordinary citizens formed ad-hoc local committees and participated in town meetings and fundraising events. Obscure Greek personalities such as Ypsilanti, Botsaris, Kolokotronis, Bouboulina and Mavrokordatos—and placenames such as Souli, Chios and Messolongi became well-known to the American public. These political and philosophical actions also had their cultural counterparts. As is well known many of the most significant poets, writers, artists, dramatists of early nineteenth century America produced works related to the Greek struggle.10 It is probably safe to say that Greek images did not enjoy the same level of name recognition again in America until the early 1960’s when motion pictures and the Onassis phenomenon captured the popular imagination.

Why did the Greek struggle capture the popular imagination? There were many reasons. America was fertile ground for such a movement. Ancient Greek language and literature was still very much part of its educational system and the debt that Western ideals owed to Classical Greek civilization was still an operative assumption in both high and popular American culture. Another factor was the fervent Christianity that dominated society. Most Americans perceived the struggle in Greece in religious terms as a battle between merciless Muslims and enslaved Christians who longed for religious freedom. Finally, we must also take into account the fact that many Americans viewed the Greek war as a struggle against tyranny similar to their own recent national revolution. Despite evidence to the contrary, they considered the Greek revolt a republican struggle against absolutism with democratic goals based on classical models. These factors were apparently known to the Greeks in revolt, and so they reinforced these impressions by writing appeals designed to flatter American sensibilities and support their preconceived perceptions.11

Although “Greek fever” was a national phenomenon it was particularly intense in New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania.12 Greek Committees were established in many cities and towns, particularly related to educational institutions and churches. Many of these groups raised significant funds by holding balls, lectures, theatrical performances and special church sermons and all social classes participated in these efforts. Even the Marquis de Lafayette, one of the great heroes of the American revolution went a speaking tour on behalf of the Greeks and helped garner national support.13 The funds collected were sent to Europe through relationships between American and European Greek Committees and up to 1825 were largely used to buy armaments and supplies for the Greek soldiers fighting for their countrymen’s freedom. Obviously, these actions did not comply with the official policy of United States neutrality. However, the government did not dare to interfere and the Ottoman authorities protested in vain about the actions of private American citizens.14 There is no accurate way to gauge the volume or true significance of this private American aid to Greece. However, it certainly amounted to millions in today’s dollars and had a very positive impact upon the Greek government and public opinion towards America judging from the documents that record the gratitude expressed at that time.

Despite the cautious stance of the Monroe administration, there were many in Congress and even in the President’s Cabinet who lobbied for an exception to be made on behalf of the Greeks. These lobbyists were informally known as the “Grecians,” and were reacting to the widespread popularity of the Greek struggle throughout the country and their own set of personal values. Thus, led by Daniel Webster, they precipitated the Great debate in Congress in January 1824.15 The debate was over a resolution to send an official American agent or commissioner to Greece, and it lasted for several days. Despite eloquent speeches the resolution was defeated. However, the “Grecians” did not give up, and an American secret agent was finally dispatched to Greece in 1825. The first one sent never even reached Greece and the second one, despite a long fact finding mission in Greece, did not accomplish anything that had the slightest influence on American policy.16

What was not known, except to a few insiders at the time, was that the United States had another secret agent in the Levant who was reporting to the President on the Greek war while trying to negotiate a commercial treaty with the Ottoman empire. He was in the region as early as 1820 and did not return to the United States until 1826.17 Similarly, the American Consul in Smyrna where Americans owned significant property and conducted a large volume of commerce, also issued reports to the State Department concerning the Greek war. In fact, Commodore Rogers, the commander of the American Squadron in the Aegean, had also been charged by the Secretary of State to expedite the negotiation of a commercial treaty with the Ottoman government.18 According to him, any action that compromised American neutrality would have severe consequences for U.S. ships and citizens in the region. Clearly, there were important commercial interests that would be threatened by the Ottoman government if they perceived any breach of American neutrality. Thus, while popular sympathy for the Greek cause was at its height throughout the U.S., commercial interests drove American foreign policy towards a course of action that if had become public would have resulted in strong condemnation by the American people. Thus, no matter how popular the Greek cause was, or how much lobbying was done by influential citizens and politicians, secret diplomacy based on the value of Turkish commerce and strategic considerations, negated all official efforts to assist the Greeks.

Clearly, even the most ardent philhellenic legislators realized that the United States was not prepared to go to war with the Ottoman empire on behalf of the Greeks. All of the debates, resolutions and lobbying did not even result in any official humanitarian aid throughout the 1820’s. The popular outpouring of support however, resulted in a brief but important relaxation of official American neutrality that led to the addition of an American built warship, the Hope—renamed Hellas—being added to the Greek Revolutionary navy. The American public was both inspired and scandalized by this so-called “Frigate Affair.” It is a complicated story in which the New York City Greek Committee helped the Greek revolutionary government hire an American firm in to build two large first-class warships for their navy. After many delays, misinformation and corruption which resulted in outrageous costs, it was necessary to sell one of the ships in order to free the other from debt. The building and arming of warships in New York for a foreign government at war with a power with which the United States was neutral was clearly illegal. Yet, the ship was allowed to sail to Greece with an American crew and with the full knowledge of President Adams who did not intervene. In this one instance, the power of public opinion and philhellenism triumphed over official neutrality.19

This unofficial act of aggression did not go unnoticed by the Sultan’s friends in the United States. Despite their efforts, a commercial treaty between America and the Ottoman empire had to wait until the end of the Greek war. It was only after the war that it was signed, sealed and delivered. A secret clause of that treaty however specified that the United States allow a certain number of frigates for the Ottoman navy to be built and supplied as part of the deal.20 Apparently, the Turks had been impressed by the Hope and wished to obtain similar warships. Thus began the military aid which continues to our own day.

Eventually, “Greek Fever” declined as news slowly reached America of the disunity, royalist sentiments, and military disasters that developed in Greece by the end of 1826. However, this did not stop American public support but transformed it. The character and purpose of private American aid changed after 1826 based on new information about the war from eyewitnesses who returned to the United States and participated in new appeals for philanthropic aid. Alarm was raised about the deplorable conditions and starvation that the Greek people were facing because of the prolonged war. A new wave of support was the result. Instead of armaments, Americans now sent shiploads of supplies to save the women and children of Greece from starvation and death. It was the first and most extensive example of American philanthropy to Europe and resulted from the deliberate actions of a small number of Americans who knew the conditions in Greece from actual experience.21

In many respects the story of the handful of heroic Americans who participated in the Greek war as volunteers is the most dramatic and interesting component of United States involvement. Although there were many merchants, tourists and seamen who passed through Greece during the war, there are approximately twenty Americans that we know for certain either fought in Greece or participated in philanthropic activities there. Very little is currently known of the activities of many of these brave men, although future research might bring more details to light. It is interesting to note, that among them was an African-American named James Williams of Baltimore, who although not quite free in his own country travelled to a far-a-way land to fight for the freedom of others.22 Of these American heroes, three individuals stand out for their devotion to the Greek struggle and contribution to stimulating American interest and aid. The trio was largely responsible for stimulating the large amount of philanthropic aid that was sent to Greece from America after 1826, and in most cases they personally participated in its distribution.

The first of these American volunteers to join the Greeks was young George Jarvis, a New Yorker who had grown up in Europe and travelled to the front with other European philhellenes in 1822. He was unique among all the westerners who went to Greece because he “went native,” to a degree more than the others, a fact that shocked many of his foreign contemporaries. Jarvis not only took the trouble to learn the language well, but he soon abandoned his western mode of life, dress and warfare and became a Greek captain (kapetanios) with a band of fighters of his own. He dressed and looked like a native, lived in the wild Greek mountains and participated in the fighting and factionalism of the Greek klephs as an equal. He became generally known as General Zervis to his Greek contemporaries who mention his heroism in their accounts of the war. Until his death in Argos in 1828, Jarvis served as the guide and authority to whom most of the other Americans in Greece relied. He has left us a remarkable journal written in Greek, English and German in which he describes his experiences; an account full of insights and information not found in any other source.23 For example, in one of his journal’s early entries Jarvis tells us of his feelings concerning the war:

August 1, 1822: “If I had not loved their common cause with all my heart, I should at this moment not have been able to resist joining them, nor do I believe anyone else who was yet able to feel for freedom and humanity. To see these poor Greeks, many without shoes, all without or with the worst of bread, joined climbing up hills and down dales, to attack the tyrannical aggressor, in defense of their country—never has an object interested me more, never did I feel more sincerely for my own family, than I did and do for the poor Greeks…”24

Although Jarvis did not travel to America during the war he contributed to the appeals for American aid that circulated among the Greek Committees back home and advised that what the combatants needed most were funds and supplies not fighting men. In fact, Jarvis is credited with urging General Kolokotronis, one of the most famous of the Greek leaders, to write a letter dated July 26, 1826, to Edward Everett appealing for humanitarian aid. This letter along with Jarvis’ missive, helped stimulate the relief efforts in Philadelphia and was reprinted and circulated throughout the country.25 The other two Americans of the heroic trio that spearheaded the philanthropic American aid effort considered Jarvis their leader, and if he had survived the war he no doubt would have played a major role in subsequent Greek-American relations.

The second American philhellene that must be mentioned was Captain Johnathan Peckham Miller of Vermont who arrived in Greece in 1824. He was known as the “Yankee Dare Devil” because of his fearlessness in battle. He too learned some Greek and wore Greek cloths, although he and his colleague, the learned and equally fearless Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, did not quite go as far as Jarvis in assimilating into Greek society. Miller returned to the United States in 1826 and by giving newspaper interviews and making speeches rallied American philanthropic aid for the suffering Greeks. The following year, he was hired by the New York Committee to return to Greece as their agent and personally distribute the supplies that had been collected.26

Howe is probably the most famous of the American Philhellenes, because he continued to be active in Greek affairs after the revolution and became a noted philanthropist and abolitionist in the United States.27 During the war he also founded an American hospital on the island of Poros and he returned to Greece after the war, founded a settlement called Washingtonia and played a role in supporting the Cretan revolt against the Turks some years later. Like Jarvis, Dr. Howe also kept detailed diary which describes his experiences in Greece and is full of valuable insights and unique information. Howe also returned to the United States 1827 to garner support for his Greek hospital and plead for aid on behalf of Greece. His public relations activities were more extensive than those of Miller, and he even went on a national speaking tour which was described in the popular press and helped attract much attention to the plight of the suffering Greeks. When he returned to Greece, he joined Miller and Jarvis in the distribution of American aid, a task that was as challenging as it was rewarding.28

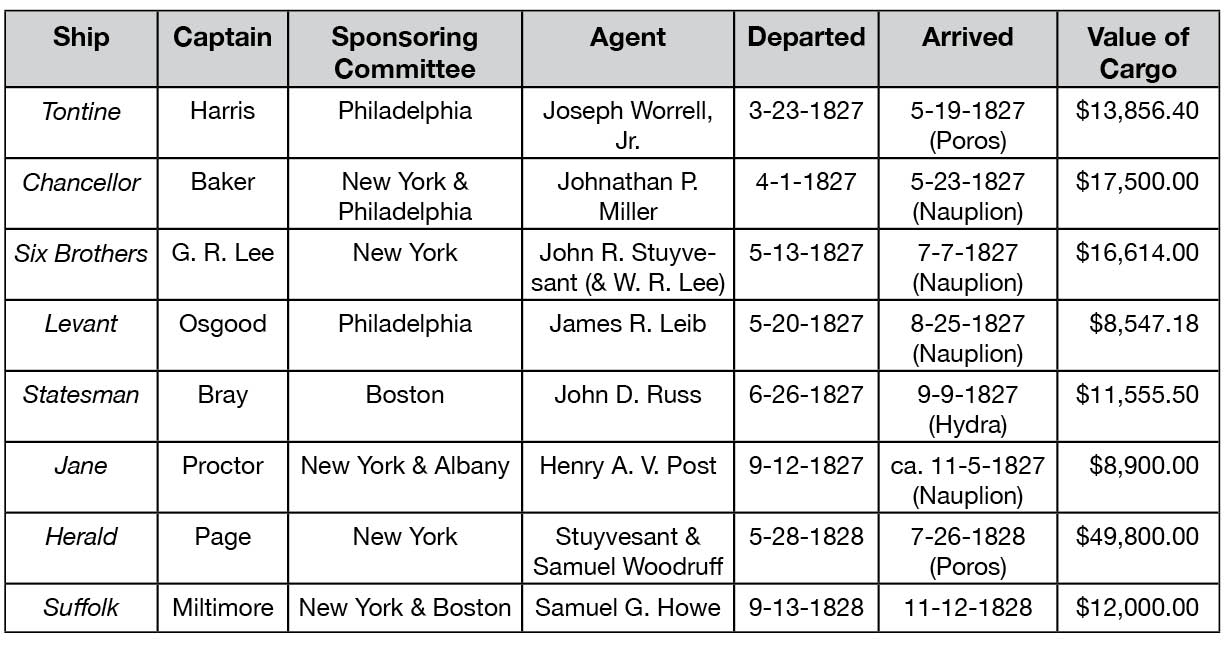

Over a two-year period, a total of eight shiploads of food, clothing, medical supplies and other items were collected and shipped to Greece utilizing American merchant ships. The most complete modern account, although brief, is given in the study by Larrabee which also contains an often reproduced chart outlining the basic information of these shipments.29 Some of the same information is also contained in a lengthy report published by Miller on behalf of the New York Committee which sponsored some of these shipments and hired the young Philhellene to supervise their distribution.30 Unfortunately, Larrabee an outstanding scholar, whose pioneering work has yet to be superseded, does not provide any documentation for his chart. Nevertheless, it is generally accurate when we can check it against Miller contemporary account, and so I reproduce it below with the hope that someone might be able to authenticate its information in a future study.

As the chart above indicates, Jarvis, Miller and Howe were aided by other Americans who accompanied the shiploads of aid and lived in Greece temporarily to make certain that American philanthropy was effectively and fairly distributed.

Some accounts were published which provide details of the goods that were collected by these Philhellenes in collaboration with Greek Relief Committees in New York, Boston and Philadelphia and the manner of their distribution in Greece. For example, Miller produced a remarkable book for the New York Committee based on his journal in 1828 entitled: The Condition of Greece in 1827 and 1828; Being an Exposition of the Poverty, Distress and Misery To Which the Inhabitants Have Been Reduced By the Destruction of their Towns and Villages, and the Ravages of Their Country, By a Merciless Turkish Foe. I believe that this is the most extensive official contemporary report issued concerning the distribution of these supplies by a Committee agent. Henry A.V. Post, also a representative of the New York Greek Committee who sailed to Greece on the relief ship Jane and distributed aid in collaboration with Miller, Jarvis, and Howe, during 1827-8, published a lengthy personal description of his experiences in Greece as part of the relief effort in 1830.31 Both works provide a vivid portrait of the conditions these Americans found, the problems they faced and the impact of American philanthropy on the desperate Greek people. Other participants either wrote newspaper articles concerning what they saw, personal letters, or brief tracts to document their work. Similarly, any ships logs, accounts by seamen and contemporary Greek descriptions that may survive have yet to be identified and exploited.32 Much of this material remains unpublished and little known, and its study and publication is vital if the full story of this important American philanthropic effort, and, especially, its impact upon Greece during some of the darkest days of its struggle against the Ottomans can be properly understood and appreciated.

The study of the methods and the difficulties of this American relief effort also help us understand aspects of the complexity of Greek society during this period, the rivalries and conflicting interests of the factions among the official and unofficial leaders of those pursuing the war, and the conflict between central governmental authorities and local interests.33 An overarching issue that surfaces again and again in connection with the distribution of the supplies is the attempt to secure them and divert them to support the military effort instead of using them to save the lives of helpless, destitute and starving civilians. Even the venerable General Kolokotronis whose letter helped publicize the need for the relief effort in order to help desperate women and children, tried to divert American aid to support his troops, as Miller informed the New York Committee in his official report.34 Another major concern that is prevalent throughout the sources is that of piracy, an aspect of the Greek struggle that is little studied.35 Like their land based counterparts, Greek ship captains were not above changing allegiances as circumstances required and resorting to piracy in order to meet the material needs of their vessels. In this connection, the naval vessels of the American squadron played a vital role in helping protect the merchant vessels transporting American aid to Greece and protecting the subsequent efforts of the Americans to distribute the supplies and transport them to where they were most needed. On more than one occasion it took an American warship to recover stolen goods or to intimidate Greek military authorities and prevent their diversion to others than those identified by American distributers as being the most in need.36 Yet, despite many obstacles the group of American philhellenes engaged in this effort to save thousands from privation, starvation and death largely succeeded with the result that many were saved that would have otherwise perished.

Surviving accounts provide many details concerning how the Americans distributed the donated supplies, the care that they took to make certain that they went to the most needy Greek families and individuals, how they protected these precious resources, and their efforts to guard against corruption and deception. In order to illustrate the aspects of these philanthropic efforts that I have outlined above and the valuable information that these American contemporary accounts contain I will quote some representative samples below, first from Miller’s report to the New York Committee and then from Post’s privately printed personal reminiscences.37

Below, Miller indicates that he could sometimes coordinate his efforts with Greek governmental authorities and that he also took advantage of whatever small opportunity he could to help individuals he accidently came across.

Poros, June 10, 1827. In the morning I received a message from the Government, requesting me to call upon them, which I did immediately, and was presented with a catalogue of eight hundred and three families, the heads of which have either been killed, or have died in the service. The widows and orphans they have collected, and are to send them to me in the afternoon, to receive clothes, shoes, and whatever else I may chance to have, to relieve their wants… The remainder of the afternoon was spent in the laborious occupation of distributing personally to those of whom a list was delivered to me in the morning by the Government.

Opened the box of clothing from Orange, New Jersey, and began distributing to those were nearly naked. In half an hour, there were collected around my quarters, at least a thousand women and children. In order to prevent any deception on the part of those to whom I should give, I placed several soldiers outside of the door, who selected those who were nearly naked, and passed them into the house, where, with the assistance of two old women, they were clothed and passed out, the soldiers taking care that they did not come a second time… [Miller, Condition, 52, 55-6].

June 16, 1827. In the evening I took a long walk on the Peloponnesian side of the island. After walking some distance in the mountains, I found a family under a tree, the mother of which was sick with fever, with four children around her. Having nothing else with me, I gave the mother two dollars, at the same time telling her that it was a donation from the ladies in America. The poor creature was overwhelmed with joy. She called upon God to bless the souls of those who had so liberally supplied her wants. [Miller, Condition, 67].

The next excerpt illustrates how this small band of American Philhellenes cooperated and worked together to achieve their goals. In it Jarvis informs Miller of what he had accomplished and indicates that even the empty barrels were valuable and kept for additional distributions.

Cenchrea, June 30th, 1827. My Dear Miller

I send by the Captain of the boat, a cargo of empty barrels which I wish you to take and store in the best manner possible…. I have distributed within four days, ninety barrels of meal and twenty-two tierces of rice to above five thousand souls, most of whom have escaped from the Turks.

They thank God and the good people of the United States, for this which prolongs for a short time their existence. I am not able to detail the whole affair for want of time. Though I have spent two or three most troublesome and laborious days, yet they have been the most satisfactory to my feelings, on account of the happiness of distributing the bounty of Americans, and the heart-felt gratitude with which it was received.

I can assure you that Corinth is in great danger, the dervans (or passes) being open, and the soldiers in great want of bread. If it please God, I shall see you within two or three days, and referring you to that time, I remain your sincere friend. GEORGE JARVIS. [Miller, Condition, 82-83].

The next excerpt illustrates the scale of what was being done and how the Americans used their contacts with local leaders to make preparations for the fair and effective distribution of the precious supplies.

July 20, 1827. ….On our arrival at Epidaurus, we found that Rhoides had got catalogues made out to the amount of three thousand souls, and had distributed the fifty-six barrels, giving to each individual four okas, (ten pounds). We distributed the whole at Epidaurus one hundred and forty barrels of meal and flour, sixteen tierces of rice, and five of Indian corn. We also distributed four boxes of dry goods, five pairs of boots, fifty-eight pairs of shoes, and half a barrel of glauber salts.

A particular description of this distribution, and the distress and misery of the population assembled at Epidauros, would fill a volume of no small number of pages. Suffice it to say, that there are at least six thousand souls assembled from different parts of Greece, now overrun by the victorious Turks. Hundreds are out in the open air without any kind of shelter but the shade of a tree. Sickness prevails among them to a great extent. We saw a fine looking girl, of about eighteen years of age, under a tree sick with a fever. She was an orphan, and a cousin was the nearest relative she had living. We gave the poor creature a blanket, clothing and rice, and medicine. There was a heavy shower of rain this afternoon. Mr. Stuyversant could not believe that the sick would be suffered to remain out during it, in the open air…

[Miller, Condition, 92-3].

Miller worked closely with Jarvis and the various American agents who accompanied the cargoes that were sent for distribution. However, he singled out one of his colleagues for special praise:

Circa August 1827: ….I here take the opportunity to remark, that no man can be better qualified for distributing food and clothing in Greece than Dr. Howe. Speaking with fluency four different languages (English, French, Italian, Greek,) possessing a benevolent heart, and firmness of character, sharing the friendship and having the confidence of all good men in Greece, he has rendered me services as agent of the Committee for which through life, I trust, I shall be grateful.

[Miller, Condition, 115]

In a letter to Miller dated Syra, October 18, 1827, Howe informed him that an American ship from Boston had been recently plundered by pirates beached on the island of Delos, a reality that constantly threatened their distribution efforts.38 The following excerpts are from Post’s unofficial personal descriptions— the first mentions the constant danger of piracy and the second highlights that local governmental authorities could not always be trusted.39

October 1827 near Cerigo island (Kythira): “…the same voice which had communicated the glad tidings of the victory of Navarino, cautioned us in the next breath to beware of the piratical vessels, which were swarming along the whole coast of Greece. The same caution was repeated to us by the captain of the British frigate Glasgow, who came alongside of us off St. Nicholas, another harbor in the island, and consoled us with the additional information, that one of our countrymen had been robbed a few days before off Cape St. Angelo (This was the Phoebe Ann of New York, which was taken into Monembasia, robbed of its cargo, and then released).” [Post, A Visit, 8].

October 1827- Napoli Di Romania (Nauplion): “Early the next morning, the governor and several other dignitaries of the town, paid us a visit…. The object of their visit was to solicit relief for the famishing multitudes that were lying within their walls. We accompanied them on shore, and after surveying with our own eyes the shocking extent of misery which prevailed in the city, and satisfying ourselves of the urgent necessity that existed for immediate assistance, delivered over to the magistrates five hundred barrels of flour, and a quantity of clothing, for the benefit of the suffering inhabitants. (The greater part of this donation, we afterwards learned, was seized by the commanders of the castles, and laid up in store for their soldiers. They had the generosity, however, to leave a hundred barrels for the use of the poor inhabitants.)” [Post, Visit, 9-10]

*He then goes to Poros which he calls the head-quarters of the Americans in Greece.

These contemporary American accounts clearly indicate that the small gallant band of Americans responsible for distributing this aid had to constantly deal with dishonest and unscrupulous Greeks who sought to steal the cargoes and use it for themselves. In fact, two American relief ships were seized or plundered by Greek military authorities who felt that the supplies would be better used to help support soldiers than starving and helpless civilians. We also know of American ships that were used to ferry supplies to support Ottoman troops fighting in Greece against the rebels. More than once, Howe, Miller and Jarvis called upon the American squadron for aid against brigands and dishonest Greek governmental authorities. Such were the complexities of the realities of Greek society and the shifting loyalties of the various factions involved in the struggle.

Post’s next series of descriptions illustrates how the distributors had to control the large desperate throngs of Greeks who gathered together to be clothed and fed using Jarvis’ small body of troops. There is also a mention of the American hospital whose role in saving lives and bringing more modern medical practices to Greece remains to be properly studied. One of the excerpts also provides insight into the little known fact that Jarvis also had to use his men to protect the supplies from greedy Greek warlords at a risk to his life and those of him small band of fighters.

November circa 16-18th 1827 near the Isthmus of Corinth. “After landing and securing the remainder of our cargo at Poros, I proceeded with a portion of it to the isthmus of Corinth, where great numbers of fugitives had assembled from different parts of the country, and were living in a state of the most shocking privation and distress…. It would require the pencil of a Hogarth to convey any tolerable idea of the squalid host that assembled around us on the beach of Kalamaki; the powers of pen and ink are incapable of anything more than a feeble sketch of the ludicrous, yet affecting, the disgusting, and at the same time interesting scene. We drew up our barrels in a hollow square, to receive the charge of the ravenous multitude, who seemed eager to devour them whole, without waiting for the dilatory process of opening and meting out portions. The confusion and contention were inconceivable. The miserable beings who had been living for months, upon no better fare than the beasts of the field, were almost frantic with joy at the unexpected arrival of wholesome and nutritious food, and many of them no doubt, would have risked their lives, in the eagerness of their impatience to secure a single oka of flour. General Jarvis, who was quartered at the time in the castle of Corinth, brought down a detachment of soldiers, consisting of ten or fifteen men, the flower and strength of his little band, to keep off the crowd, and maintain some order in the distribution. To effect this, they were frequently obliged to have recourse to violence, for nothing but beating could keep the people within any bounds; but the soldiers took delight in it, painful as the necessity was, and made a frolic of sallying forth from their tambouri (breastwork) of barrels, with long rods with which they armed themselves for the occasion, and putting to flight unresisting groups of women and children. I shall never forget the feelings with which I was agitated, when surrounded by this vast assemblage of poverty and misery: even the brutal Turk, if such a thing were possible, would have felt his heart bleed and his bowels within him, on beholding the awful desolation which his own hands had wrought. There were old men, grey with years and sinking under the infirmities of age, there were mothers with helpless infants screaming at their breasts, — there were virgins in the prime of their days,— and there were children without number, in the season of playful innocence, all exhibiting the same emaciated and death-like countenances, all clad alike in rags, and covered with filth and vermin, the unavoidable consequences of their homeless and destitute condition. Many among the hapless throng had seen far better days, had been nursed in the lap of plenty, had been clothed in soft raiment, and had eaten and drunk at the table of luxury. Even to those who had been brought up in indigence, and accustomed to struggle with the ills of poverty, the present conflict was indeed dreadful and appalling; but oh! It was enough to melt the heart that had never before known one tender emotion, to see the delicate forms of well-bred females, crouching upon the cold ground, and shivering beneath a scanty covering of soiled and tattered garments, to behold their eyes haggard with grief, and their cheeks pale and wan with hunger and disease; and to hear the cries of distress which would ever and anon break from them in the agony of despair. It was affecting, almost beyond endurance, to hear the tales of woe which these houseless fugitives related to us; how they had fled from the blaze of their dwellings, and found refuge in some mountain retreat, from the swords of their blood thirsty pursuers; how they had seen their friends and families butchered before their eyes, and led away into a captivity more terrible than the most tormenting death; and how they themselves had been wandering up and down the land, ‘seeking rest and finding none’ and suffering under toils and privations, that had reduced them to the forlorn conditions in which we beheld them.

We were so occupied for three days in the distribution of our cargo; and as nearly all the people had come from a distance, those of them who had not received their portions were obliged to remain the intervening nights, in the open air, with no other shelter than what was afforded them by a few low and straggling bushes, and many of them without a mouthful of food of any kind. The weather was cold, and wet, and boisterous, and it seemed as if nothing short of miraculous power could save these poor creatures from perishing… [Post, A Visit, 19-21].

November 1827, Loutraki: “Mounted upon Jarvis’ Bucephalus, and escorted by the General himself on foot, I rode across the isthmus to Loutraki, a miserable village at the foot of Mount Geranion, composed entirely of small huts and sheds, the temporary habitations of the wretched fugitives whom we fed at Kalamaki. We entered several of these abodes of misery, and witnessed scenes of diversified suffering too painful to dwell upon, even in recollection…. As we retraced our way down the mountain, and beheld for the last time the wretched objects that lay starving and shivering around us, we felt rejoiced that we had been the instruments of contributing, in however a small degree, to alleviate their calamities; but it was the sad and chilling reflection, that hundreds of them must perish ere long…” [ Post, Visit, 23-25]. “Sunday, the 25th of November, was a day rendered memorable in Poros by the consecration of the American Hospital. In order to inspire the people with confidence in the institution, it was necessary to humour their superstition so far as to have the building sprinkled and fumigated, and dedicated to the Panagia, after their own fashion. The important ceremony was performed by the Bishop of Damala, and was honored by the presence of the venerable Miaules….” [Post, Visit, 34].

[Dec. 18, 1827] …. In the evening, Jarvis returned from an excursion into the mountains, upon which he had set out the day before, for the purpose of ascertaining the condition of the people, and of directing the manner of their assembling at Armiro. The degree of suffering he found to be quite as great as had been represented to us. Thousands of miserable beings were collected about the villages, and were living in caves and clefts of the rocks, in a state of utter destitution, ready to perish for want of the simplest and commonest necessaries of life. They were principally fugitives from other parts of the country,— exiles from their native homes, who had fled from the desolation of their fields, and were now endeavoring to drag out a wretched and hopeless existence, by mean which humanity sickens to contemplate…. [Post, Visit, 80-1]

…The four following days we employed in feeding the starving multitudes that were constantly pouring down upon us from the mountains. The number of persons to whom we administered relief, was about eighteen thousand— principally women and children, and old men, from Coron, Modon, Navarino, and the other Messenian towns. Such scenes of heart rendering misery as were here compelled to witness, it is almost impossible to conceive, surrounded as were are in our favoured land by the blessings of peace and plenty… . It will be sufficient to say, that the suffering at Armiro, was of the same affecting character as that which existed at Corinth, but far exceeding it in extent, as comprehending a far greater number of victims… [Post, Visit, 83].

Though undisturbed by the Turks, we suffered no small annoyance from unruly Greeks, and particularly from a wild and eccentric Moreote Captain, named Staikos, who has several times distinguished himself during the war by acts of great personal valour… This Staikos was quartered with General Niketas, somewhere between Kalamata and Karitena, and the moment he heard of our arrival, flew with all speed to Armiro, with the hope of securing something for one half of the cargo should be distributed among the soldiers of Niketas. He next professed a most violent sympathy for the poor people of about Karitena, and urged very strenuously that three to four hundred barrels should be laid aside for them in some cave or other convenient place, promising to take charge of it himself, and have it safely delivered to them. Indignant at the rejection of these pacific proposals, he now took a warlike attitude, and sternly ordered us off the ground, threatening compulsory measures, if we refused to obey. He had about twenty soldiers with him, which was nearly double the number of our own force; but Jarvis, nothing intimidated by the odds that were against him, bravely called out to his men who had possession of the tower, and told them, if Staikos was determined to have war, to let him have it. Guns were cocked and presented on both sides, and a battle seemed unavoidable; but Staikos’ courage became somewhat cooled by this show of determined resistance, and after a few hot vollies of words, he withdrew his forces…..

….the following day. He again made his appearance, raving with chagrin and disappointment, and ordered us away, as before,— beat the unarmed and unoffending peasantry, who were waiting to receive their portions, and drove them about from place to place,— and once leveled his musket within a few feet of Jarvis, and would have shot him dead if he had not been prevented in time. He remained the whole day upon the ground, doing his utmost to annoy us in every possible way… [Post, Visit, 84-5].

Post concludes this description of the distribution of American aid with the following statement:

….But as to the poor people, who were the immediate recipients of our bounty, they uniformly evinced the most unaffected and heartfelt gratitude; and I have no doubt, that the friendly aid and sympathy of the American people, has left behind it in Greece a respect and admiration for the American name, which will not soon be forgotten. [Post, Visit, 86-7]

Overall, Post’s account is full of insightful comments on a wide variety of subjects based on his careful observations and interactions with many Greeks and non-Greeks during the great struggle for Greece’s liberation. He comments upon their localism and their naïve reverence for their glorious ancestors notes their way of life, the beauty of the landscape and curious religious practices. Despite all of the faults of the Greeks he dealt with and the hardships their actions brought upon him, Post remained an ardent Philhellene devoted to their cause. For example, at one point he discusses why so many so-called Philhellenes who flocked to Greece became disillusioned and how others come to have negative views.

…These Philhellenes, moreover, had not taken into consideration the perils and privations they were destined to encounter; they found that they must sleep hard, and fight hard, and fast long and often; that to be fellow-workers with the Greeks, they must also be fellow-sufferers with them; and that the highest recompense they could expect for their generous self-devotion, was the consciousness of befriending a good cause, and perhaps an honorable death in the lap of glory. These disappointments naturally filled them with chagrin, mortification, and disgust; and nothing was heard from their mouths but bitter anathemas against the ungrateful Greeks—the Greeks unworthy of liberty, unworthy of sympathy and common charity.

There are other travelers again, who take pride in vilifying the Greeks, for no other reason than to show themselves exempt from the weakness of classic enthusiasm….

….There is yet another set of men who constitute a very powerful body of Mishellenes; I allude to the naval officers, captains of merchant vessels, supercargoes, etc.. whose duties call them to the Levant. These generally visit for a short time some one or more sea-ports, and from a very limited observation among the most vicious and degraded portion of the Greek nation, venture to pronounce a sweeping denunciation against all who bear the name.. [Post, Visit, 258-9]

Elsewhere, Post is clear about why he feels the Greeks deserve aid and support and his view is not based on sentimentality nor blind allegiance: He writes that: “We intend not, therefore, to advocate the character or cause of the Greeks, on the ground of their moral excellencies; we waive all claims founded on such pretentions; we concede the point, that that they are far from being a perfect race……” However he concludes that:

The cause of the Greeks, whatever may be their individual character, is one which no disinterested and reflecting man can fail to approve and admire. It is the cause of liberty against tyranny; of the religion of Christ, though under a corrupted form, against a still more corrupted form of the most ruthless and unyielding fanaticism that ever desolated the earth; of an oppressed people, only requiring the advantages of freedom and education, in order to become a useful and respectable member of the family of nations, against an empire of barbarous and brutal despotism….

At a time when murder, and robbery, and every other crime, enjoyed full license and impunity in Greece, and when every one was crying out to me, that there was a “lion in the way”—that thieves and assassins were before me, looking out for prey,—I travelled the wild mountain path with only a single, unarmed attendant, and found no danger or cause of alarm: instead of insult or injury, I received nothing but a peaceful and respectful salutation from the peasantry and soldiery that I encountered as I passed along. As a comment upon the faithlessness and treachery so often charged upon the Greeks, I shall only observe, that instances are known, not only to myself individually but to a number of other Americans, of devoted fidelity and scrupulous honesty on the part of servants and attendants, which we might perhaps look for in vain among any other people…

[Post, Visit, 264-66]

We know that at least eight American ships loaded with food, other supplies and clothing were sent to aid the starving populations of Greece between 1826 and 1827. Although exact figures are elusive their cargos had an estimated value in excess of $100,000 at the time. I estimate the number of Greeks saved from immediate starvation based on accounts similar to Post’s and Miller’s, could have been as many as over 200,000 people.

In one of his writings about the struggle, Edward Everett, America’s greatest Philhellene, who was also a scholar, a congressman and president of Harvard University, sought to give an answer to the question of why should America send aid.40 His answer was that it did not matter that the struggling Greeks were the ancestors of the giants of classical civilization, but that Americans should care about them because of their common interest in Liberty and Virtue. Thousands of his countrymen apparently agreed with him and ignored commercial interests and official government neutrality, to send aid to a people yearning to be free. This was the most significant American contribution to the Greek cause.

Footnotes

1 This paper supplements and expands upon some of the ideas contained in my book Founded on Freedom and Virtue: Documents Illustrating America’s Contributions to the Greek Revolution (2005) and subsequent conference presentations and lectures. I wish to express my thanks to Dr. Christos Ioannides and Dan Georgakas for inviting me to contribute to this volume; and to my teachers, the late John A. Petropulos, John C. Alexander and John Koliopoulos for introducing me to the fascinating complexities of this period of modern Greek history.

2 I owe many of these ideas to the introductory essay by John A. Petropulos to the volume entitled: Hellenism and The First Greek War of Liberation (1821-1830): Continuity and Change, edited by Nikifors P. Diamandouros et.al., (Institute for Balkan Studies-156, Thessaloniki: 1976) 19-41. I have deviated from the commonly used and in fact contemporary identification of these events as a revolution in order to call attention to issues all too often ignored in recent historiography. As Petropulos noted in his 1976 introduction, the term revolution is problematic because it is questionable how revolutionary in fact the result was; war of independence holds similar problems since the resulting state was only independent in a formal sense; thus, a war of liberation is more accurate bearing in mind that only a portion of the Greek people were in fact liberated from Ottoman rule at that time. One must also recognize that there were many previous Greek revolts against foreign rule often relying upon foreign intervention and support that proved unsuccessful. Concerning this, the classic study of Konstantinos Sathas, Tourkokratoumene Hellas [Turkish Held Greece] (Athens: 1869,) is still useful and has been supplemented by volumes of Apostolos E. Vakalopoulos, Istoria tou Neou Ellenismou [The History of Modern Hellenism] vols. 2-4 (Thessaloniki, 1964-1974); the first volume was published in English as The Greek Nation 1453-1669 in 1976 by Rutgers University Press.

3 Our sources make clear that the borders of what was geographically considered “Greece” varied during this period, although the parameters of what generally constituted ancient Greece continued to have great influence. A comprehensive and detailed study of the cartography, terminology and geographic works of what the term Greece encompassed prior to the establishment of the modern Greek nation state remains to be done. One can get a sense of the issues involved by consulting Christos G. Zacharakis, A Catalogue of Printed Maps of Greece 1477-1800 (Samourkas Foundation, Athens: 1992). See also the theoretical perspective of Artemis Leontis, Topographies of Hellenism: Mapping the Homeland (Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London: 1995). For one important and classic approach to the problem of what constitutes Greece from a state building perspective see Douglas Dakin, The Unification of Greece 1770-1923 (Ernest Benn Ltd, London: 1972).

4 See the chapter by John A. Petropulos, in Foreign Interference in Greek Politics: An Historical Perspective (Pella Publishing Company, NY: 1976), 15-24.

5 Two recent publications on the subject are: David Brewer, The Greek War of Independence (The Overlook Press, Woodstock& N.Y: 2001) and Thanos Veremis, et. al., eds., 1821: E gennese enos ethnous-kratous [1821: The Birth of a Nation-State] vols 1-5 ( Ethnike Trapeza, Athens: 2010) have proven unsatisfactory for a variety of reasons and barely mention the subject of American aid.

6 Recently Angelo Repousis has added to the work of previous scholars, see Chapter 3, “The Cause of Freedom and Humanity,” in his Greek-American Relations from Monroe to Truman (Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio: 2013), 42-56; and has also placed the 1821 period in the broader diachronic political context. A full study of this nineteeth century American philanthropic aid utilizing all of our extant sources however remains a lacunae.

7 Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou, ed., Founded on Freedom and Virtue: Documents Ilustrating the Impact in the United States of the Greek War of Independence 1821-1829 (Artistide Caratzas, Publisher, New York & Athens: 2002).

8 A brief account of this American aid is given in Robert L. Daniel, American Philanthrophy in the Near East 1820-1960 (Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio: 1970) 1-16; and a fuller account by Stephen A. Larrabee, Hellas Observed: The American Experience of Greece 1775-1865 (New York University Press, New York: 1957).

9 George G. Arnakis and Eurydice Demetrakopoulou, eds., George Jarvis: His Journal and Related Documents. Americans in the Greek Revolution. Volume I (Thessaloniki, Institute of Balkan Studies: 1965); and George G. Arnakis and Eurydice Demetrakopoulou, eds. Historical Texts of the Greek Revolution: From the Papers of George Jarvis. (Austin, Texas, Center for Neo-Hellenic Studies: 1967).

10 See the bibliographic outline in Hatzidimitriou, Founded on Freedom and Virtue, 369-375. To which one must add the many articles on various aspects of this movement in the United States by Steve Frangos published in the English editions of the National Herald newspaper such as for example, his “Greek Aires and 1821 War Relief,” National Herald, June 10, 2014; and the recent book by Angelo Repousis, Greek-American Relations cited above where an updated bibliography can be found.

11 Americans who opposed aiding the Greeks were quick to point out that the European powers favored monarchy and had strong ties to factions within the Greek leadership who supported anti-republican sentiments. See the classic study of John A. Petropulos, Politics and Statecraft in the Kingdom of Greece 1833-1843 (Princeton University Press, New Jersey: 1968), 1-106, concerning these factions and their ties to England, Russia and France; and the comments of Repousis, Greek-American Relations, 34-38.

12 For the important role played by Philadelphia philhellenes see Angelo Repousis, “The Cause of the Greeks: Philadelphia and the Greek War for Independence, 1821-1828,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography vol. CXXIII, No. 4 (October 1999) 333-363.

13 Repousis, Greek-American Relations, 43.

14 See Repousis, Greek-American Relations for the best overview of all of the political aspects. The classic study of the national outpouring of American philhellenic support is by Myrtle A. Cline, American Attitude Toward the Greek War of Independence 1821-1828 (Atlanta, Georgia: 1930); to which one must add, Paul Constantine Pappas, The United States and the Greek War for Independence 1821-1828 (East European Monographs, Boulder: 1985). The opening chapters of Larrabee, Hellas Observed, are also full of important insights concerning the context and development of American interest in Greece.

15 For selections of the texts of these debates see: Hatzidimitriou, Founded on Freedom and Virtue, 209-57.

16 The agent was William C. Sommerville who unfortunately never reached Greece. He was succeeded by Eastwick Evans who did actually go to Greece and reported on the war. Commodore John Rodgers, the senior naval commander of the American Mediterranean fleet also sent back secret dispatches on the war to the U. S. State Department.

17 It was Luther Bradish who was trying to negotiate the commercial treaty—see, Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 49-51, 151.

18 See John H. Schroeder, Commodore John Rodgers: Paragon of the Early American Navy (New Perspectives on Maritime History and Archaeology. University Press of South Florida: 2006). Also, Charles Oscar Paullin, Commodore John Rodgers: Captain, Commodore, and Senior Officer of the American Navy 1773-1838: A Biography (The Arthur H. Clark Company: Cleveland, Ohio: 1910) 335-352. For examples of some of Rodgers’ reports see, Hatzidimitriou, Founded on Freedom and Virtue, 258-80, 372.

19 The best account of the Frigate Affair is given in Pappas, The United States and the Greek War. A selection of the many press accounts of the scandal is given in Hatzidimitriou, Founded on Freedom and Virtue, 288-311.

20 For the text of the treaty see: J. C. Hurewitz, ed., The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics: A Documentary Record vol. I European Expansion 1535-1914 (New Haven and London, Yale University Press: 1975) 246-7. The context has recently been touched upon by Michael B. Oren, Power, Faith and Fantasy: America in the Middle East 1776 to the Present (W.W. Norton & Company, New York: 2011) 114-118.

21 Robert L. Daniel, American Philanthropy in the Near East 1820-1960 (Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio: 1970) 1-16; Repousis, Greek-American Relations, 42-51.

22 Repousis, Greek-American Relations, 44-5. Concerning these Americans see: William St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free: The Philhellenes in the War of Independence (Oxford University Press, London: 1972) 280-1, 334-41.

23 See my comments above concerning the need for further studies of Jarvis’s contributions and references to the work of Arnakis in note number 9.

24 Arnakis-Demetracopoulou, George Jarvis 97.

25 Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 150.

26 Larabee, Hellas Observed, 150-1.

27 See the recent study of Howe by James W. Trent, The Manliest Man: Samuel G. Howe and the Contours of Nineteenth Century American Reform (University of Massachusetts Press: 2012).

28 Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 153, 157.

29 Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 148-175; The chart is on page 149.

30 Col. Jonathan P. Miller, The Condition of Greece in 1827 and 1828; Being An Exposition of the Poverty, Distress, and Misery to Which the Inhabitants Have Been Reduced by the Destruction of Their Towns and Villages, and the Ravages of their Country, by a Merciless Turkish Foe. As Contained In His Journal (Printed By JH & J Harper, New York, 1828). One should also note that Miller’s actual journal and other papers if they survive, have not been studied or published. Like Jarvis, Miller’s contributions and life have not been the subject of any detailed study—and remains a subject that some future scholar should address.

31 Henry A. V. Post, A Visit. Greece and Constantinople in the Year 1827-8 (Sleight & Robinson, Printers, New York: 1830). One should also note that Post indicates that he also produced sketches during his travels, none of which are reproduced in his book. His manuscript material might prove highly informative if it survives and is studied in connection to his important book.

32 For example, see Howe’s diary and Stuvesant’s newspaper article; excerpts given in Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 155 -6.

33 For a good overview of these complexities, see: John S. Koliopoulos and Thanos M. Veremis, Greece: A Modern Sequel (Hurst & Company, London: 2004) 11-43.

34 Miller, Condition, 45.

35 Kyriakos Simopoulos, Pos Eidan Oi Xenoi Ten Ellada tou’21 [How Foreigners Viewed Greece in 1821] vol. 5; 1826-1829 (Athens: 1984) 495-509.

36 Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 157. The much larger British naval flotilla also dealt with many of the same issues; see: Lieutenant-Commander C. G. Pitcairn Jones, R.N., ed., Piracy in the Levant 1827-8: Selected From the Papers of Admiral Sir Edward Codrington, K.C.B. (Printed for the Navy Records Society, London: 1934).

37 Both Larrabee and Simopoulos consider Post’s account of the American distribution effort and its impact the most interesting of our surviving information. See Larabee, Hellas Observed, 158-163; and Simopoulos, Pos Eidan Oi Xenoi, 204-5, 409-444, who devotes an entire chapter to Post. Simopoulos also has some interesting comments on American policy in general, see pages 351-360.

38 Miller, Condition, 131.

39 Miller, Condition, 136, verifies that Post had been duped into giving provisions to the authorities in the Morea that he describes as “a den of thieves.” He was able to contact the ship (the Jane) and provide guidance and protection so that the error would not be repeated.

40 Concerning Everett, see Hatzidimitriou, Founded on Freedom and Virtue, xxvii-xxiv. His still unpublished travel journal to Greece in 1819 has appeared in a Greek translation with scholia by: Anteia Phrantze and Stathis Phinopoulos, Edtourant Everet: Selides Hemerologiou [Edward Everett: Pages From His Journal] (Trochalia, Athens: 1996).