Recognition of Greece after 1821?

U.S. Congress Says “No,” Haiti Says “Yes”

(Public domain via National Gallery of Art)

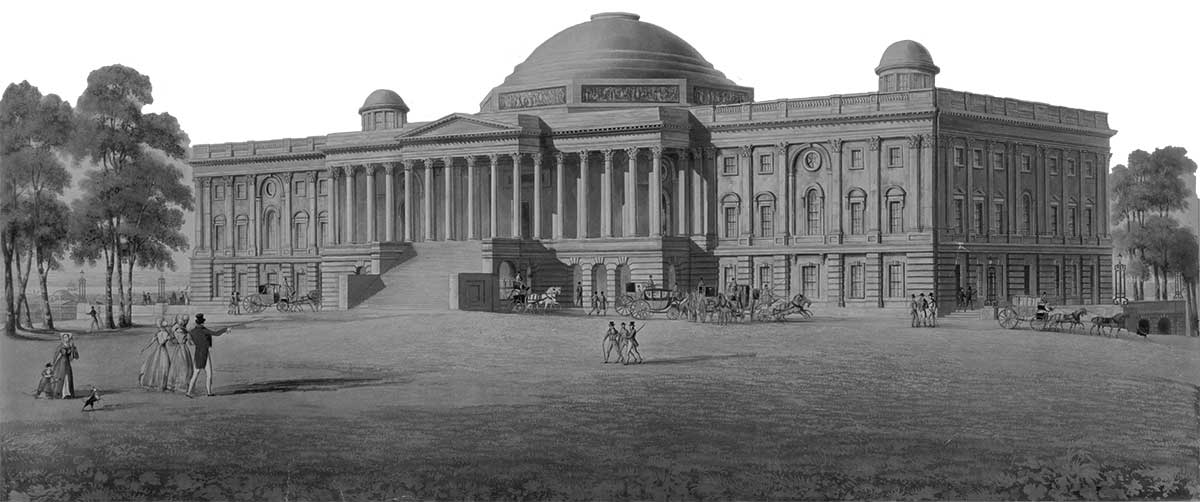

An 1823 painting of the House of Representatives, where Daniel Webster and Henry Clay sought to get the United States to recognize the independent state of Greece.

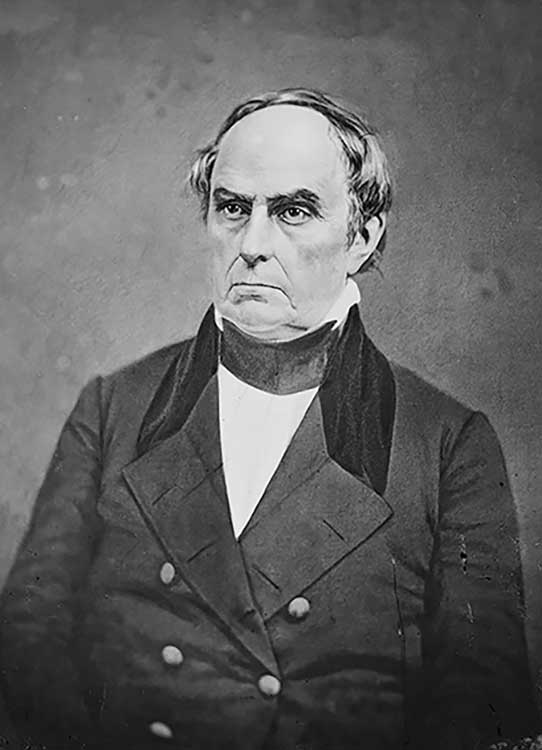

After President Monroe formally rejected the Greek request for direct intervention, Congressman Daniel Webster (1782–1852) of Massachusetts, the most articulate philhellene in Congress, stood in the well of the House of Representatives to argue for a formal Congressional endorsement of the Greek independence movement. He motioned to have the U.S. government send an official envoy to assist the Greeks in their struggle for independence.

In a lengthy well-reasoned argument on January 19, 1824, Webster maintained that Americans needed to support Greece. He stressed U.S. national interests for defending the republican form of government under international law, in a world dominated by monarchies. Following Webster, Congressman Henry Clay (1777–1852) of Kentucky also gave an impassioned speech, and in his remarks called upon the people of America not to allow such wrongs and sufferings to be imposed upon the Greeks who are a “Christian” people. The resolution did not pass, and Webster and Clay dropped the matter.

Eventually, in 1825, when Henry Clay was Secretary of State under John Quincy Adams, he sent an agent to Greece, who died in Paris before arriving. Clay did not make any efforts to send another agent to Greece. He did, however, send the envoy John Rodgers to survey the situation, but more with an eye toward the negotiation of commercial treaties with the Ottoman government.

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

U.S. Congressman from Massachusetts, Daniel Webster.

(Public domain via Hathi Trust)

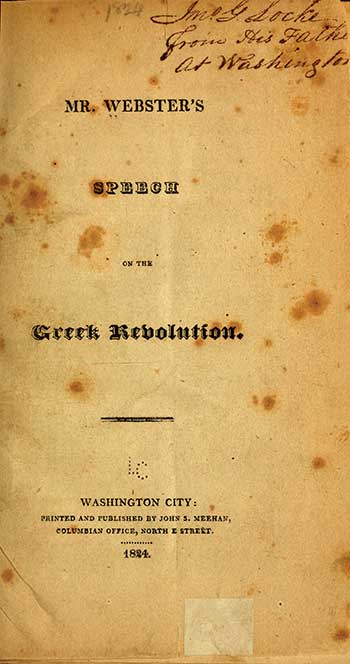

Resolved, that provisions ought to be made, by law, for defraying the expense incident to the appointment of an Agent or Commissioner to Greece, whenever the President shall deem it expedient to make such an appointment.

~ Mr. Webster’s Resolution to Congress

December 8, 1823

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

U.S. Congressman from Kentucky Henry Clay.

Go home, if you can; go home, if you dare, to your constituents, and tell them that you voted it down;

~ Henry Clay

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

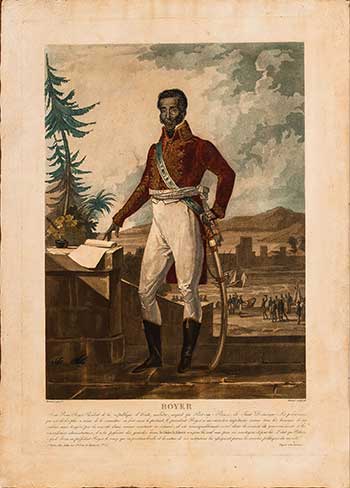

President Jean-Pierre Boyer (1776–1850) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution, the slave revolt that resulted in the independent state of Haiti.

Haiti: The First Country to Recognize

the Independent Greek State

Two years before the U.S. Congressional debate, on January 15, 1822, Haiti was the first country to recognize the independence of Greece. President Jean-Pierre Boyer, in a letter to the Greek revolutionaries in Paris, including Adamantios Korais, proclaimed the Greeks “citizens,” indicating they were no longer Ottoman subjects but members of a new independent polity. Boyer explained that had the Haitians not been facing dire financial problems of their own, they would have surely helped the Greeks.

Such a beautiful and just case and, most importantly, the first successes which have accompanied it, cannot leave Haitians indifferent, for we, like the Hellenes, were for a long time subjected to a dishonorable slavery and finally, with our own chains, broke the head of tyranny.

~President Jean-Pierre Boyer, President of Haiti

(Public domain via Clark Art Institute)

President Jean-Pierre Boyer was the second president of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He was sworn in in the provincial capital of Port-au-Prince. Painting by Adolphe-Eugène-Gabriel Roehn, 1818.

Citizens! Convey to your co-patriots the warm wishes that the people of Haiti send on the behalf of your liberation.

~ President Jean-Pierre Boyer, President of Haiti

(Public domain via Library of Congress)

Capitol of the U.S. at Washington ca.1825 from the original design of the architect, B.H. Latrobe, Esq.. Engraving by T. Sutherland.